Parasztbecsület és Bajazzók a New York-i Metropolitan Operában – a 2016. január 25-i előadásról KŐRY ÁGNES tudósítását olvashatják

Részletes zenei beszámolót terveztem a Metropolitan Opera Parasztbecsület–Bajazzók-produkciójának január 25-i előadásáról, de tervemet módosítanom kell: zenei vonatkozásban csak benyomásaimról tudok írni, részletekről nem. Január 23-án kellett volna megérkeznem New Yorkba, ezért szereztem jegyet a január 25-i előadásra. Sajnos a rendhagyó New York-i időjárási viszonyok megzavarták tervemet: a város teljesen hó alá került január 23-24-én, szombaton és vasárnap, minek következtében minden közlekedési eszközt betiltottak, s így a repülőgépek sem szállhattak le egyik New York-i reptéren sem. Eredeti tervemhez híven elmentem ugyan a január 25-i előadásra, de rögtön a nagyon kellemetlen és a vártnál hosszabb London–New York-út (és az ezzel járó huszonnégy órás kényszerű ébrenlét) után. Ilyen körülmények között nem vállalkozom részletes zenei elemzésre – ám a Met és az előadás mindezek ellenére is erőteljes benyomást tett rám.

Nem tudom, milyen közönség gyűlik össze premierestéken a nagyon szép, elegáns, modern épületben, amely 1966 óta otthona a Metropolitan Opera társulatának. Azt viszont tudom, hogy látogatásom napján a közönség hétköznapi ruhákba öltözött, lelkes operarajongókból állt. Koncentrációjuk, fegyelmezettségük, a műfaj és alkalom iránti tiszteletük nyilvánvaló volt. Cserébe a Met is tiszteli közönségét: mindenki számára jár az ingyenes, de részletes, valóban tartalmas műsorfüzet (hasonlóért a londoni operaházakban borsos árat kérnek).

London és Budapest operaházaitól eltérően a Met nem alkalmaz színpad feletti feliratozást; az előadást nem zavarja az operához nem tartozó függelék. Viszont minden ülőhely előtt (vagyis minden szék hátán) egy képernyő található, amelyen több, választható nyelven olvasható a szövegkönyv fordítása – az amerikaiak és az angolul nem beszélő/értő turisták is követhetik a dráma (vagy komédia) szövegét.

A londoni operházaktól eltérően, a súgóknak fontos szerepe van a Metben. Tíz súgót alkalmaz a Met; ez alkalommal Donna Racik adott segítséget a súgóárokból. Az előadás végén Racik szép tapsot kapott a szólóénekesektől. Ilyesmi nem fordul elő Londonban, ahol nincs se súgó, se súgóárok, s így tízszemélyes súgó-lista sem a műsorfüzetekben.

A Met zenekari árka nem olyan mély, mint a londoni és budapesti operaházakban, így a zenekar hangzása jobban egybeolvad a színpadi hanggal. A zenekari játékosok így vélhetően jobban érzik, hogy az előadás egészéhez tartoznak, nem csupán annak egy részét alkotják.

A Par–Baj-párost negyvenöt éven keresztül Franco Zefirelli rendezésében játszotta a Met társulata. Ezután kérték fel Sir David McVicart, hogy 2015 áprilisára új koncepcióban állítsa színpadra a műveket. A Parasztbecsületet McVicar az 1900-as évek körül játszatja, tehát csak néhány évvel az opera keletkezése után. Viszont a Bajazzók McVicar koncepciójában az 1940-es évek végére kerül: a Parasztbecsület falujában játszódik, de két generációval később. Érdemes megemlíteni, hogy a Metropolitan Opera annak idején elsőként párosította a Parasztbecsületet (bemutató: Róma, 1890) és a Bajazzókat (bemutató: Milánó, 1892), vagyis elsőként állították színpadra egy estén a két operát 1893-ban. Így tehát teljesen logikus, hogy McVicar egyetlen összefüggő egészként kívánja színre hozni a két darabot a Met színpadán.

A Parasztbecsület díszlete egyetlen magas téglafal, a szövegkönyv szerint ez a templom fala. Ez a fal megmarad a Bajazzókban is, de itt a falu külső falát ábrázolja. A Parasztbecsületben McVicar és kreatív csoportja (díszlet: Rae Smith, jelmez: Moritz Junge, világítás: Paule Constable) elképzelése nyomán a színpad mindvégig majdnem teljesen sötét, mindegyik szereplő jelmeze fekete. Ha nem tudnánk, hogy a dráma húsvét vasárnapján játszódik, azt gondolhatnánk, hogy éjjeli történetről van szó. A kopár koncepció már az előadás legelejétől nyilvánvaló: nincs függöny, azonnal sötétséget és ürességet látunk. Néhány széktől eltekintve a színpad üres, habár a közepén van egy forgó pódium, ami elég sokszor lendül mozgásba (hogy a jelenetváltozásokat érzékeltesse).

A Bajazzókban továbbra is marad a falusi tér, de itt (a 20. század közepén) már elektromos és telefonkábelek is láthatók. A színpad közepét egy nagy teherautó foglalja el, telepakolva bőröndökkel, díszletekkel, jelmezekkel és minden mással, amire egy vándortársulatnak szüksége lehet. McVicar egy függönyt is alkalmaz az előadás során: sötétkék, csillagokkal díszített, meglehetősen kirívó függönyt. Meg is ijedtem: csak nem ez lenne a Met állandó függönye? De nem: úgy látszik, McVicar ezzel a függönnyel a történet színházi jellegét akarta hangsúlyozni. Tonio ez előtt énekli el a Prológot. A színpadon nincs hiány színekben: Canio majdnem rikitó kék öltönyben jelenik meg először, így jelenti be társulata színpadi előadását a falu lakosságának. Nagyon sok a mozgás, szín és színházi tréfa; McVicar sokféle szórakoztató eszközt használ. A „színház a színházban” nagyon mulatságos, de tragikus is (amikor a történetben gyilkosságra kerül sor). Állítólag McVicar a Bajazzók egészét vaudeville-ként rendezte meg. Nem ismerem ezt az énekes-zenés vígjátéki stílust, nem tudom, milyen sikeresen alkalmazta McVicar. Azt viszont tudom, hogy valóban szórakoztatott, mégpedig ízlésesen.

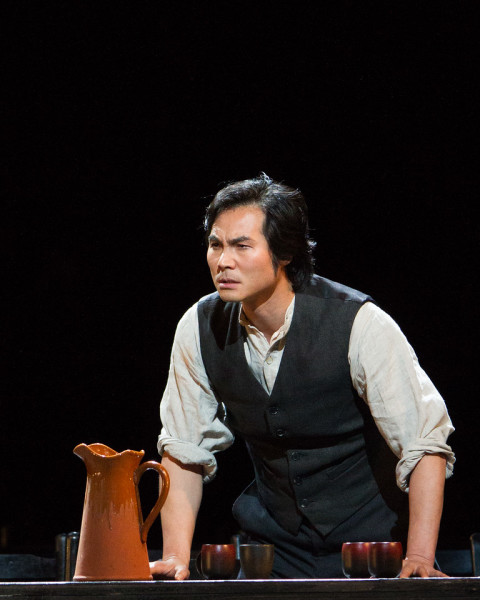

Végül, de nem utolsósorban néhány szó az előadás zenei megvalósításáról! Fabio Luisi karmester előadásmódja szenvedélyes, de nem hisztérikus, lírai, de nem engedékeny. Szigorúan követi a partitúrát, ugyanakkor inspirálja énekeseit és zenekarát. Violeta Urmana (Santuzza) imponáló wagneri hangulatot teremtett, Lee Yonghoon (Turiddu) megerőltetés nélkül sziporkázott, Barbara Frittoli (Nedda) teljesen meggyőző volt zeneileg és drámailag is. Roberto Alagna (Canio) nyílvánvaló közönségkedvenc – első megjelenését nyíltszíni taps köszöntötte –, és valóban nem lehet letagadni sztár-kvalitásait. De magas hangjai bizony erőltettek (és ezért egy kicsit durvák) voltak. A zenekar és a kórus kiválóan követte és valósította meg maestro Luisi inspiráló vezetését és instrukcióit; a Met gyerekkórusa is színvonalasan állt helyt (Anthony Piccolo karigazgtó irányításával – nomen est omen).

A magas színvonalú előadásnak hála a borzalmas utazás és a huszonnégy órás kényszerű ébrenlét ellenére sem aludtam el a Met kényelmes nézőterén. Ennél nagyobb dicséret talán nem is érhet egy operaelőadást!

Fotók: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera

Cavalleria Rusticana/Pagliacci, The Metropolitan Opera, New York, 25th January 2016

By Agnes Kory

What was planned as a detailed review of The Metropolitan Opera’s double bill – Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci – has to be changed into a report of impressions. I was due to arrive at New York on Saturday 23rd January 2016 and thus arranged a seat for the double bill on Monday 25th January. However, unusual weather conditions in New York modified my plan. New York was snowed under on Saturday and Sunday: all transport was suspended (even forbidden) in the city; flights could not land at the airport.

My scheduled visit to the Met materialised but immediately after a very unpleasant journey from London to New York (and after 24 hours of sleep deprivation). Reporting about nuanced details of performances in either of the two operas forming the double bill is sadly not possible under such circumstances. However, my impressions are still powerful.

I do not know what first night audiences are like in the beautiful, elegant and modern building, which has been home for the Metropolitan Opera since 1966, but on the night of my visit the audience seemed to consist of ordinary opera lovers in ordinary clothes. Their attention, discipline and evident respect for the opportunity to experience these performances were striking. In reverse, the Met respects its audiences. Members of the audience are handed substantial programme notes – modestly referred to as cast lists – free of charge (yet such detailed programme notes are heavily charged for in London opera houses).

Unlike in London and Budapest, no surtitles are shown above the stage which thus remains undisturbed by elements not forming part of the performance. However, there is a screen in front of each seat; surtitles in various languages can be switched on and off by each seat holder. Hence locals as well as non-English speaking tourists are catered for.

Unlike in London opera houses, prompters play an important role at the Met. Indeed, ten prompters are employed by the company; this time Donna Racik supported the singers from the prompt box (and was duly acknowledged and applauded by the singers on conclusion of the performances).

The orchestra pit is not as low as in London and Budapest opera houses, thus the sound coming from the pit is more integrated with the sound on the stage. Presumably orchestra players might feel more part of the whole than when playing much lower down.

After keeping Zefirelli’s production of ‘Cav and Pag’ in repertoire for some 45 years, Sir David McVicar was given the task to create a new staging for the Met in April 2015. He sets the action for Cavalleria Rusticana around 1900, a few years after the opera’s composition. However, McVicar moves the setting of Pagliacci to the late 1940s, apparently intending to create the sense that the story takes place in the village of Cavalleria Rusticana but two generations later. It is of note that the Metropolitan Opera was the first opera company to present Cavalleria Rusticana (premiered in Rome 1890) and Pagliacci (premiered in Milan in 1892) together in 1893. Hence McVicar’s attempt to unify the two operas on the Met’s stage is logical. The initial set, showing tall brick walls which indicate the church in Cavalleria, remains in place for Pagliacci but here functioning as the outside walls for the village square.

For Cavalleria Rusticana McVicar and his design team (with Rae Smith‘s sets, Moritz Junge‘s costumes and Paule Constable’s lighting) created a very dark scenario. The stage is dark all way through and all costumes are black. If one did not know that the story was played out during the day of Easter Sunday, one could have been forgiven thinking that all actions took place during the night. The starkness is evident right from the start as the stage is open: no curtain is used; we are immediately confronted with darkness and emptiness. The stage is bare, except for some chairs and, as it soon transpires, for a revolving platform which turns quite a lot to indicate scene changes.

In Pagliacci the village square remains but this time (in mid-20th century) electric and telephone wires hang down. The centre of stage is occupied by a large truck, piled high with suitcases as well as sets, costumes, and all what was necessary for a touring company of actors. For Pagliacci McVicar uses a curtain – in a rather vulgar blue colour (initially giving me concern that perhaps this is the regular Met curtain) – as if to emphasize the theatricality of the plot. Indeed, Tonio’s Prologue is sung in front of this curtain. There is no shortage of colour on stage. Canio appears in a bright blue suit to announce the forthcoming theatrical event. The stage is full of action, full of colour and full of theatrical gags in true entertainment mode. The play within the play is as funny as is tragic (when the plot turns murderous). Apparently Mcvicar gave vaudeville treatment to the whole of Pagliacci. Being unfamiliar with the vaudeville style, I would have not recognised this concept. However, the entertainment value was evident, regardless any particular theatrical style.

At last but not least a few words about musical impressions on the night. Conductor Fabio Luisi’s approach was passionate but not hysterical, lyrical but not indulgent, committed to the score but clearly inspiring singers/orchestra players. Violeta Urmana (Santuzza) reached impressive Wagnerian depths, Youghoon Lee (Turiddu) offered effortless brilliance, Barbara Frittoli (Nedda) was totally credible musically as well as dramatically. Roberto Alagna (Canio) is loved by the Met audience (who burst into applause at Alagna’s first entrance to the stage) and, indeed, he has star quality. However, his top notes were slightly strained (and thus harsh). Orchestra and chorus splendidly responded to Maestro Luisi’s inspired conducting, and the Met children also stood their ground (under the guidance of their aptly named chorus director Anthony Piccolo).

The high-quality performances made it worthwhile (and made it possible) for me to stay awake after my dreadful London-New York journey and 24 hours of sleep deprivation.

Thank you, Met!

Photos by Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera